How many steps are there between a judge and a scientist? The first profession was the one that Maria Carolina Gonzalez aspired to as a child. The second was the one that she embraced and that brought her from Buenos Aires, Argentina, to Brazil and – within the country – to the Edmond and Lily Safra International Institute of Neuroscience (IIN-ELS), of Santos Dumont Institute (ISD), in Macaíba (RN).

Since she was little, the girl dreamed big: in addition to being a judge, she also thought about becoming a doctor. The paths taken, however, were different, and initially followed according to the subjects she had the most affinity with at school.

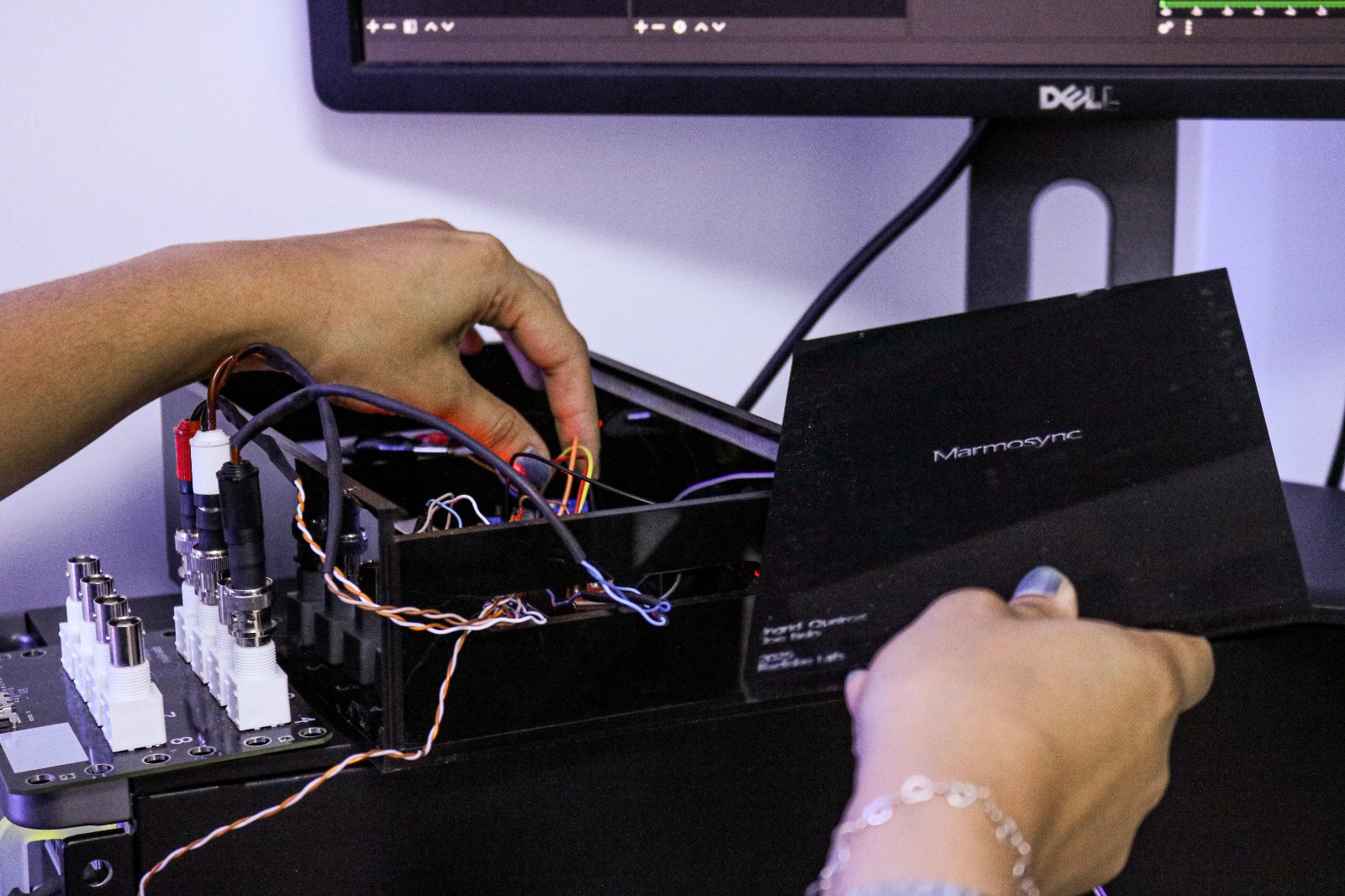

The girl's history with science began at an early age, realizing that she had a connection with the area, which made sense in choosing to major in biotechnology, an area in which she graduated from the National University of Quilmes, in Argentina. Carolina is currently 36 years old, is a professor of neurophysiology and researcher at IIN-ELS since 2019. She has a PhD from the University of Buenos Aires with experience in neurophysiological mechanisms involved in the formation, expression and modification of memories. The Argentinean is co-author of two articles recently highlighted in international scientific publications, examples of research where she tries to answer “how to prevent traumatic memories from taking control of behavior and preventing a normal life?” “How do some memories last longer than others?” and how are memories updated?”, among other questions.

A new possibility for modifying traumatic memories is the result of the article “mTOR inhibition impairs extinction memory reconsolidation”, which was on the cover of the American magazine Learning & Memory, in January 2021. The second featured article of the year, “GluN2B and GluN2A-containing NMDAR are differentially involved in extinction memory destabilization and restabilization during reconsolidation”, suggests a mechanism for keeping traumatic memories repressed and was published in the journal Nature Scientific Reports. The two works were written in partnership with researchers Andressa Radiske, Martin Cammarota, Diana Nôga, Janine Rossato and Lia Bevilaqua, from Memory Research Laboratory Brain Institute (ICe) from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN). Both have Radiske as the main author.

Science in the Northeast

In a scenario in which many Brazilians seek opportunities in other countries, the Argentinian arrived in Brazil in 2014, where she began working with memory studies in her post-doctorate at Memory Research Laboratory, of Brain Institute.

What did you want to be when you grew up?

Well, when I was a child I wanted to be a judge, but I also really liked biology and natural sciences. At school, an organic chemistry teacher, who was very good, suggested visit the National University of Quilmes, I had a degree in biotechnology, and I really liked the curriculum. At that time it was an area that was very popular in relation to gene therapy and genetic manipulation to improve and interfere with health, make new medicines... I became interested and studied biotechnology as an undergraduate.

And how was this leap from wanting to be a judge as a child and ending up going into the field of science and research?

I wanted to be a judge, then I started wanting to be a doctor along the way, but to work in the research area, not so much in the clinical part. There is no specific reason for following the path in a different degree, it just happened. Back in Argentina, when you finished elementary school you could choose different areas to continue in high school, for example, natural sciences, social sciences, economics, arts and at the school where I studied I ended up turning to biological and exact sciences, areas with which ones had the greatest affinity.

Tell me a little about your academic and professional trajectory…

My initiation into research was during my undergraduate studies when I started working with Professor Liliana Semorile in the molecular microbiology laboratory, studying the mechanisms of resistance to antibiotics in bacteria. However, in my final year, I took a course with Professor Diego Golombek, where I had my first contact with Neurosciences, I started reading articles about memory and found it fascinating. After that, I told the professor about my identification with the area and he recommended me to postgraduate studies with a researcher called Jorge Medina, a renowned neuroscientist in Argentina. From this contact, I began to do my doctorate researching the mechanisms involved in the persistence of memory, seeking to understand why some memories last longer than others. Jorge collaborated with researcher Martín Cammarota who was in Porto Alegre at the time and, during my doctorate, I spent a few stays in Porto Alegre and started working with him as well.

When I finished my PhD in Physiology in Argentina, Martín was moving his laboratory to Natal and I signed up for the Sciences without Borders Program, which at the time wanted to attract young talents and it was from there that I arrived in Natal, in 2014. It was then that I started to be part of the Memory Research Laboratory, coordinated by researchers Martín and Lia Bevilaqua, and in 2019 the opportunity arose at IIN-ELS, where I am to this day.

UN data shows that women represent only 28% of researchers in the world. What does this data reflect on your career as a researcher, how did you feel about it?

Particularly, in the laboratories I passed through, women were always the majority or were present in the same proportion as men, despite it being common for there to be more men in these spaces.

At any point – whether as a student or researcher – did you feel that there was no space for you in this area? What led you to move forward?

I've never felt that in any of the work environments I've been in. In the laboratories I was part of I always felt super supported, motivated and heard. But in other contexts, I have noticed situations that reveal prejudice, for example, at conferences or conversations with colleagues, where I was next to an equally qualified researcher and the questions were only directed to him.

Here at ISD we have many female students and women doing research, investing in science in the most diverse areas – neurosciences, maternal and child health, rehabilitation… Do you see that this “minority” scenario of women in science has changed?

Yes, I think there is a change in attitude, not only among women, but in younger generations, like my students, I observe in them that there are no traces of gender prejudice.

In Brazil there is a movement of students/researchers to emigrate to other countries. For example, we have masters who graduated from ISD and are doing their doctorates in Germany, in the United States... And you made the opposite move, you came here from Argentina. What motivated you to come here? What does it mean to you to be doing science in the Northeast of Brazil?

For me, doing science here is a challenge. I came here trusting in a project that aimed to encourage young people and also with a team idea, to form the Memory Research Laboratory. The idea is to do quality science using the tools we have available, developing interesting solutions. Not to mention that I really like Natal, which is a quiet city, with a very good climate and friendly people.

Why did you decide to research memory?

Many people begin to study memory due to a personal connection with the topic, for example, a relative who had Alzheimer's disease. But I don't have that personal identification. What interests me about studying memory is that there are several very relevant questions that have not been answered, for example, how do some memories last longer than others? How are memories updated?

One of my objects of study, for example, is knowing how to prevent traumatic memories from taking control of behavior and preventing a normal life. Remembering certain traumatic memories all the time can cause anxiety and that's not cool. So, the objective of our work is to understand the mechanisms that help us inhibit fear memories. How can these memories be repressed? It doesn't mean they disappear, they are there, but not constantly dominating behavior.

A recent article you wrote – in partnership with UFRN – was on the cover of the January edition of the American magazine Learning & Memory. Explain it to me simply: what does this study show?

This study that we carried out in partnership with UFRN shows the mechanisms behind keeping traumatic memories repressed. We used an animal model to simulate an artificial traumatic memory, in a laboratory context.

For example, let's say you left your house and around the corner from your house you are robbed in a somewhat violent way. You get scared and that's super normal, you went through a bad time, but you need to leave the next day. You pass the corner, remember what happened and feel anxious, afraid but you pass and see that nothing happens. You continue passing by, you don't forget what happened, but you create another inhibitory memory (the extinction memory) when the bad episode continues not to happen and thus, your fear, the expression of your traumatic memory becomes lessened.

In this study, we discovered that a protein called mTOR – in Portuguese, mechanistic target of rapamycin – regulates the production of another protein, Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor, which is essential for aversive or traumatic memories to remain repressed by the memory of extinction. We observed that inhibition of the mTOR protein prevents the persistence of extinction memory and causes fear to return.

What does this discovery represent for society? What impact could it have?

Our discovery is very important because it allows us to better understand the mechanisms responsible for keeping these undesirable memories inhibited. This knowledge can be applied to the development of new strategies or drugs that enhance psychotherapies based on the process of memory extinction, which aim to alleviate the symptoms of patients with anxiety disorders.

______________________________________________

International Day of Women and Girls in Science wants to encourage gender equality

In 2015, February 11 was declared the International Day of Women and Girls in Science in a partnership between the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) and UN Women. The organizations' aim was to encourage women's participation in science, recognizing a lack of gender equity in the sector. According to data from UNESCO, women represent around 28% of researchers around the world.

For the professor-researcher at IIN-ELS, one of the greatest challenges in promoting gender equality is that women increasingly occupy spaces of power, where today men are the majority.

“I think what still makes it difficult is that many of the spaces of power are occupied by men, mostly, when there are women who are equally qualified, but who suffer prejudice. In many situations, the people who are most listened to and taken into consideration are men,” said Carolina.

Still according to the most recent data from UNESCO, men publish more articles, have more main authors and are cited more than women: during 2014, for example, among the most cited authors in research in the world, only 13% were women.

The reality at the Santos Dumont Institute points to the prospect of change in these data. In the Institute's postgraduate courses, Master's in Neuroengineering and Multiprofessional Residency in Health Care for People with Disabilities, pioneering programs in Brazil, 56% of active students in 2020 were women. Furthermore, in the scientific works published in 2020 by ISD students, women were present as authors and co-authors in 36 of the 47 scientific productions published.

Health research

Most of the works published in the last year are a reflection of ISD's work in science and health, where professors, researchers, master's students and residents develop solutions in different areas, with emphasis on health. At the Anita Garibaldi Health Education and Research Center and the Edmond and Lily Safra International Institute of Neurosciences, research and innovation are instruments of interprofessional work in providing health care to the population.

For the doctor in Health Sciences and manager of Anita/ISD, Lilian Lira Lisboa, science is present on all fronts of the Institute's activities. “At Anita we work with science in different ways, be it multi-professional preceptors or residents, as we are linked to teaching, research and extension and all of this is science. So, all the women here work for science, for evolution, for the development of a fairer society”, said the manager of the Anita Garibaldi Education and Research Center, Lilian Lisboa

Text: Kamila Tuenia / Ascom – ISD

Edition: Renata Moura / Ascom – ISD

Photograph: Kamila Tuenia / Ascom – ISD

Communication Office

comunicacao@isd.org.br

(84) 99416-1880

Santos Dumont Institute (ISD)

It is a Social Organization linked to the Ministry of Education (MEC) and includes the Edmond and Lily Safra International Institute of Neurosciences and the Anita Garibaldi Health Education and Research Center, both in Macaíba. ISD's mission is to promote education for life, forming citizens through integrated teaching, research and extension actions, in addition to contributing to a fairer and more humane transformation of Brazilian social reality.